Discovering New Species Through Tropical Reef Biodiversity Research

Jul 19, 2015

Smithsonian marine biologist Carole Baldwin leads the Deep Reef Observation Project (DROP), an effort to study biodiversity—the variety of species—and monitor changes in deep tropical reefs, highly diverse but underexplored ocean ecosystems.

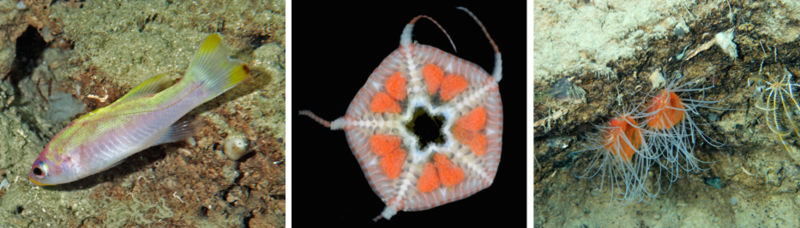

Off the coast of Curacao in the southern Caribbean, Carole and her team of almost 40 Smithsonian researchers are uncovering a new world of biodiversity that science has largely missed. Using a manned submersible, they have discovered at least 50 new species in an area of only around 0.2 square kilometers.

Coral reefs are home to more than 25% of all marine life. In addition to their great biodiversity, or variety of species, coral reefs possess tremendous economic value. Human communities depend upon them for food, new pharmaceuticals, tourism, recreation, and barriers against rising sea levels.

However, the same human communities that benefit from coral reefs also threaten their existence. Pollution, the introduction of invasive species, and warming waters resulting from global climate change all risk severely damaging ocean ecosystems.

As Carole explains, “Earth is an ocean planet full of amazing life forms that have adapted to every imaginable condition. It is up to each of us to protect this vital resource. Our lives really do depend on it.”

Most of our knowledge about coral reefs comes from studies of shallow coral reefs. We know comparatively little about tropical depths, between 150 and 1,000 feet, which are home to mesophotic, or “middle light,” and deeper reefs.

Carole and her team seek to understand these relatively unexamined environments and provide research that will aid marine conservation.

“Until DROP, we didn’t know much about deep reefs, which are essentially in our own backyards,” Carole says.

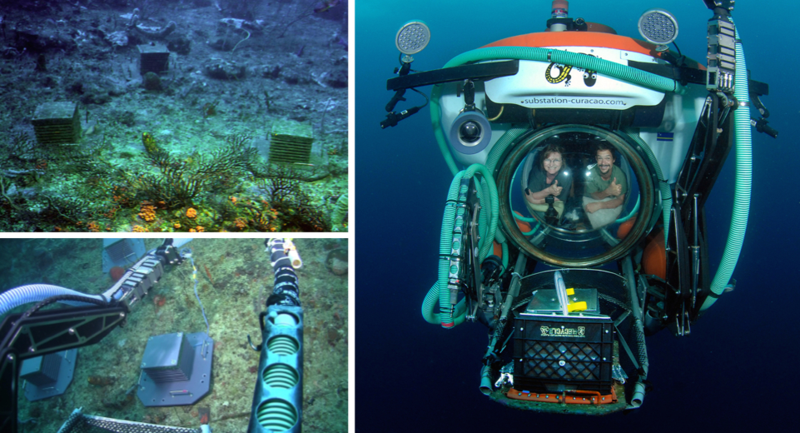

Taking advantage of the proximity of deep waters immediately off the Curaçao coast, the submersible Curasub allows Carole and 4 others to quickly dive down to as far as 1,000 feet below the surface. The Curasub’s robotic arms collect sea creatures which the crew then brings to the surface for scientific study.

Using tissue samples harvested from specimens collected with the Curasub, Carole and her DROP team use modern DNA techniques—including DNA barcoding—to help determine which species captured represent previously documented species and which ones are completely new.

DROP scientists take tissues samples from creatures collected with the submersible, then compare short DNA sequences and anatomy of these samples with those of known specimens from Smithsonian and other collections. If they can find no match, then DROP can add a formerly unlisted species to the record.

This Smithsonian project offers rich opportunities for education and outside research. Once identified, the project’s samples join the collections of the National Museum of Natural History as a resource accessible to further study. High school, college, and graduate students help process the data collected by DROP and play an important role on the teams working in Curacao and in Washington, D.C.

In addition to documenting the biodiversity of deep reefs, DROP is collecting the baseline data needed to recognize long-term changes in temperature and some components of reef communities by placing temperature loggers and autonomous reef monitoring structures (ARMS) in areas on a shallow-to-deep reef slope off Curacao.

ARMS act like condos for a reef’s “hidden biodiversity,” the small creatures and algae that grow, burrow, and hide in the cracks and crevices of reefs. Each ARMS comprises a stack of 10 evenly-spaced plastic plates placed in and around the study area of interests for a specific period of time, when marine creatures take up residence in the ARMS.

After 1, 2, or even 5 years, researchers retrieve the ARMS unit, separate each of the plastic plates, and photograph them. Next, they identify, record, and DNA sample all of the species living on them. State-of-the-art next-generation DNA sequencing methods are invaluable in this effort. The ARMS are then deployed to collect data for another pre-determined period.

Equipped with the information recorded from the first year of ARMS sets and the temperature loggers, DROP scientists now have the beginnings of two globally unique data sets. Although ARMS units have been placed on shallow coral reefs in many parts of the world, and much is known about temperature fluctuations on shallow reefs, there are no long-term environmental and biological data sets that monitor conditions on a shallow-to-deep reef profile…until now. Through DROP, Smithsonian is emerging as a leader in exploring and monitoring tropical deep reefs, perhaps the most diverse underexplored ecosystems in the ocean.

In Curacao and the Caribbean, DROP has already changed the ways we understand deep reefs—and will continue to do so. Soon the project will expand its area of observation to include offshore locations with a research vessel, the R/V Chapman, a retrofitted ship that will be able to launch the Curasub from new locations in the Caribbean.

DROP anticipates that Curacao will become part of a growing Smithsonian network of coastal marine monitoring sites, MarineGEO, where our scientists “take the pulse of the ocean,” through ARMs, temperature loggers, and other environmental and biodiversity monitoring.

Through MarineGEO sites around the world, the Smithsonian is creating a system for comparing coastal ecosystems globally to help us better understand ecosystem response to global climate change. Unlike other sites in the network, Curacao offers the ability not only to monitor changes in shallow coastal ecosystems but also in deep ones. DROP’s monitoring activities are especially timely, with the global decline of coral reefs and little understanding of the role deep reefs may play in the survival of shallow reefs above.