See How Science and Government are Ensuring a Future for Myanmar’s Eld’s Deer

Jul 19, 2015

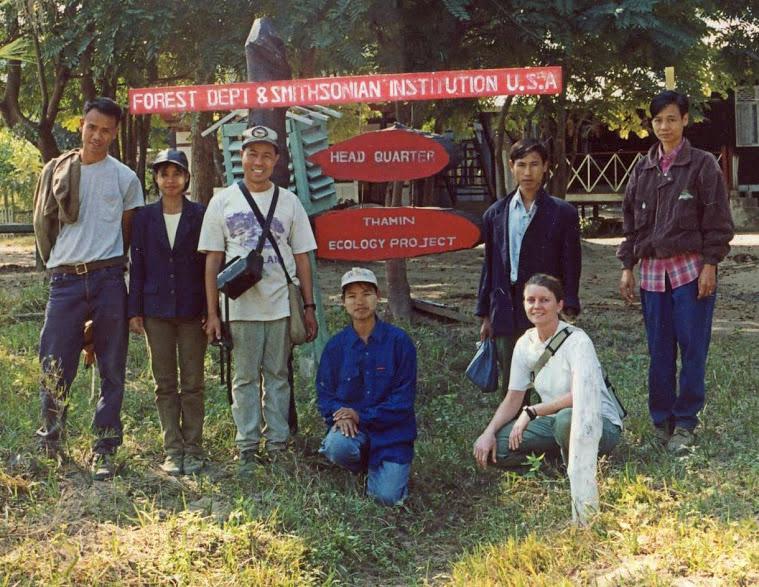

In partnership with Myanmar protected area staff, Smithsonian researchers have conducted extensive research at Chatthin Wildlife Sanctuary in northern Myanmar. A team of researchers used a combination of radio-tracking and survey techniques with geospatial data to establish a baseline of biological data that can be used to track population trends and inform wildlife management decisions.

For more than two decades, Smithsonian scientists have worked to conserve the critically endangered Eld’s deer, a species that once ranged throughout Southeast Asia from Vietnam to India, but today has only an estimated 2,500 deer remaining in the wild, primarily in Myanmar and Cambodia. Researchers led by Bill McShea, Melissa Songer, and Peter Leimgruber mapped the remaining dry tropical forest habitat that the Eld’s deer depend on and used the map to locate a previously unknown population of Eld’s deer in the wild.

Increasing pressure from agriculture, logging, and other human activities put these forests at risk — making the future of Eld’s deer uncertain. That’s why Smithsonian scientists are working hard to find ways to reverse the deer’s recent trajectory of decline.

With help from their Myanmar colleagues, Melissa and Peter have documented pressures on forest resources, including harvesting of timber and hunting Eld’s deer by communities around Chatthin. By learning how local communities depend on the forest for critical resources such as food, shelter, and medicine, we can work together to find ways to reduce impact on the dry forests without negatively impacting people. This work links conservation science with human communities, pointing the way towards possible solutions through alternative livelihood development.

Smithsonian scientists bring a global perspective that enhances research and paves the way towards government support for the conservation of the Eld’s deer and other critically endangered species. Bill is Co-Chair of the Deer Specialist Group of the Species Survival Commission (SSC), a group tasked by the International Union for the Conservation of Nature (IUCN) to track the conservation status of 65 deer species worldwide.

In addition to his research on the Eld’s deer, Bill studies white-tailed deer in the Eastern United States. Nearly hunted to extinction in the 1920s, successful wildlife management has increased the white-tailed deer population to more than 25 million today.

The growing numbers of white-tailed deer, with their voracious appetite for oak seedlings and many other plant species, has resulted in a dramatic reduction of oaks in eastern forests and threatens many wildflowers.

“It’s important to see both sides of the conservation story: what happens when deer decline too much, as in Myanmar, or when they increase too much, as in the Eastern U.S.,” Bill explains. “You can see from what happened with the white-tailed deer that with the right protections in place, the Eld’s deer could recover and could be part of a human-natural landscape mosaic in Myanmar.”

![[file:field-caption] [file:field-caption]](https://global.si.edu/sites/default/files/styles/wysiwyg/public/6419957059_50cd2ee7de_b-486x730.jpg?itok=Rf58IDoz)

Smithsonian scientists didn’t stop with research—they worked with governments to ensure solutions identified in the research were implemented. Smithsonian scientists consulted with the Government of Myanmar to develop a new Eld’s Deer Conservation Plan and worked with the Government of Norway to provide new funding for Chatthin Wildlife Sanctuary and other Eld’s deer sites in Myanmar.

Conservation research on Eld’s deer continues at the Smithsonian Conservation Biology Institute (SCBI) located in Front Royal, Virginia. Here scientists Steven Monfort and Pierre Comizzoli have developed techniques for artificial insemination and in vitro fertilization for Eld’s deer.

In 2011, the first Eld’s deer fawn was born at the Khao Kheow Open Zoo in Thailand from an in vitro fertilization process developed at SCBI.