Saving Endangered Cheetahs in Namibia and Around the World

Jul 26, 2015

Smithsonian cheetah biologist Adrienne Crosier works with the Cheetah Conservation Fund (CCF) in Namibia from her lab at the Smithsonian Conservation Biology Institute (SCBI) in Front Royal, Virginia. With her partners, she studies how cheetahs reproduce in order to create new technologies to improve cheetah reproduction in human care. As a result of this work, there are now hundreds of samples of genetic material banked to help restore cheetahs to the wild and reintroduce genetic diversity to the cheetah population. Adrienne’s research at SCBI increases our understanding of cheetah biology, better equipping conservation biologists to save cheetahs from extinction.

Cheetahs are the fastest land animals in the world. They are also the most endangered African cat. Growing human populations and the breakdown of their habitats threaten cheetah populations from Namibia to Iran. In 1900, almost 100,000 cheetahs roamed freely from the southernmost tip of Africa all the way to Persia. Today, there are between 10,000 and 12,000 cheetahs worldwide, including in the wild and in human care.

The largest cheetah populations live in the southwestern Africa countries of Botswana, Zambia, and Namibia, where the CCF is working to protect the world’s remaining cheetahs. Smithsonian Cheetah biologist Adrienne Crosier works from her lab at SCBI to study how cheetahs reproduce and create new technologies to better breed cheetahs in human care.

Compared to other animals, cheetahs have a very low genetic diversity. About 12,000 years ago, a mass extinction event eliminated 75 percent of the world’s large mammal species. A few cheetahs survived this event, and all cheetahs today are descended from this small group.

The reduction in cheetah genetic diversity from this mass extinction event, called a “population bottleneck,” means that cheetahs are particularly vulnerable to environmental changes in their habitats and face significant challenges to reproduction.

Advances in reproductive understanding of cheetah populations, combined with biobanking of cheetah genetic material, mean that Smithsonian scientists like Adrienne and our international partners can increase the genetic diversity of the cheetah population by reintroducing genetic material from cheetahs who died 10, 20, or even 30 years ago.

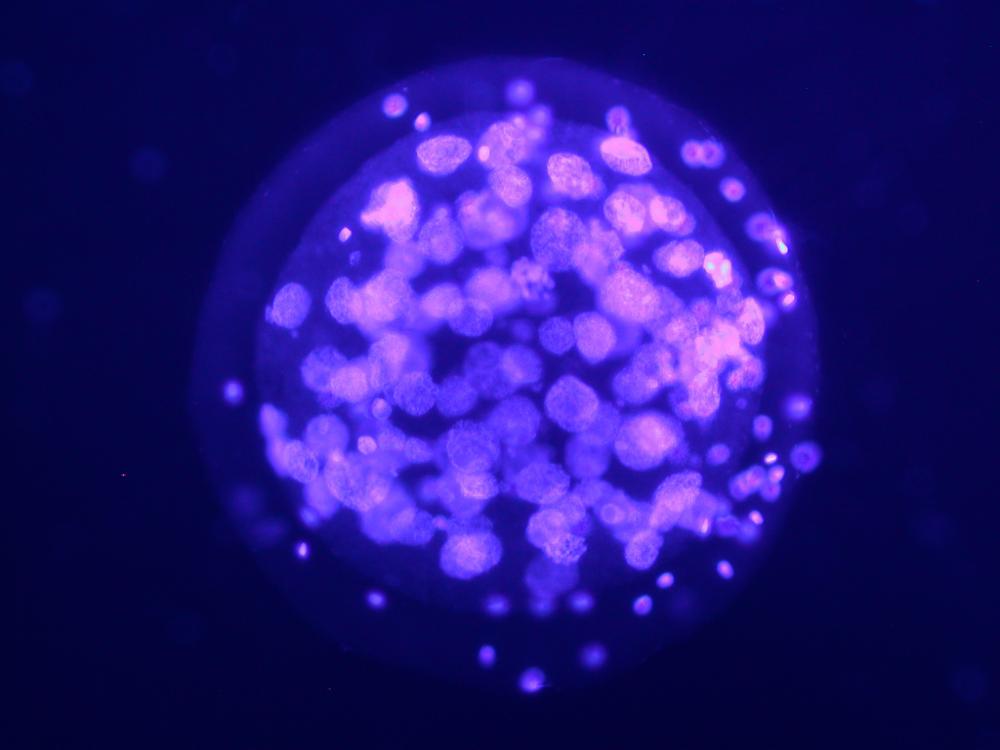

Since 2002, Adrienne has worked to train local Namibians how to collect biological samples from cheetahs and “bank” them in a biobank repository where they are frozen for future use. There are now hundreds of samples of cheetah genetic material banked in Namibia, which can be used to restore cheetahs to the wild and to reintroduce genetic diversity to the cheetah population.

Today Adrienne’s research focuses on the reproductive physiology of older female cheetahs. Female cheetahs have irregular reproductive cycles and scientists don’t really know how to manipulate female cheetah hormones to increase reproductive ability. Because cheetah habitats are threatened and their natural prey base is decreasing, Adrienne’s research is critical to preserving cheetah populations.

By biobanking the eggs of older female cheetahs unable to have offspring, Adrienne and her team can later fertilize and implant these eggs into surrogates, thereby reintroducing those genetic traits into the general population.

Adrienne combines her research in reproductive health with the research of other SCBI conservation biologists on cheetah health, disease, and genetics to better understand the threats to cheetahs in the wild and in human care. By observing how cheetahs reproduce in human care, Adrienne and her team can explore how we can better preserve cheetah habitats to encourage and support cheetah populations.