Satellite Whale Tracking Yields International Protection for Panamanian Humpbacks

Feb 15, 2016

Whether we realize it or not, ARGOS positioning satellites play a role in many people’s everyday lives. Without them, modern communication would not be possible, and they’re increasingly put to work in important scientific studies. One Smithsonian scientist used their tracking capability to contribute key data for new environmental policies in Panama designed to protect sensitive marine life off its shores.

Teeming with fish, crustaceans, birds and other sea life, the Gulf of Panama is a rare marine treasure. With easy access to food and protected by the many coves and inlets that dot the coastline, an estimated 1,000 humpback whales convene annually from as far south as Antarctica to breed and give birth.

The area is also one of the great shipping passages of the world, and growing ever busier. More than 17,000 commercial ships cross the gulf each year traveling to and from the Panama Canal and port facilities. That volume of traffic, combined with a high concentration of whales, inevitably leads to collisions. During a period of two and a half years, over 13 whales were killed, most by large shipping vessels.

Based at the Smithsonian Tropical Research Institute (STRI) in Panama, marine biologist Hector M. Guzman works to understand how human activity impacts tropical marine species and the sensitive ecosystems they inhabit. Since 2003, Hector has been using satellite-positioning tags to track marine life in the waters around Panama and other countries in the region. These tracking tags revealed details about how humpback whales travel throughout the gulf to their feeding areas in the Antarctic Peninsula and Chile. Hector was able to use those data to inform new marine protection policies in Panama.

Hector started tracking whale movement in 2008 to gain a greater understanding of whale behavior and habitat use in the area and their interactions with ships. In Panama’s Las Perlas Archipelago, nearly in the center of the gulf and south and west of Panama City, Hector and his research team identified more than 300 individual humpback whales that take up temporary residence there every year. Over six seasons, Hector tagged 60 whales from Ecuador to Costa Rica in order to compare their movements with the known courses of 1000 individual ships.

“It is a magic tool,” Hector says of satellite tagging. “From any place I am in the world, I can connect and see my whales. Compared to being in a boat or observing from a cliff with binoculars, there’s no way you can compare the amount of data we are producing on a daily basis.”

During one period, over half of the tagged whales had 98 close encounters with 81 different ships—in just under two weeks. Ships were coming into contact with the breeding humpback whales more often than anyone had recognized.

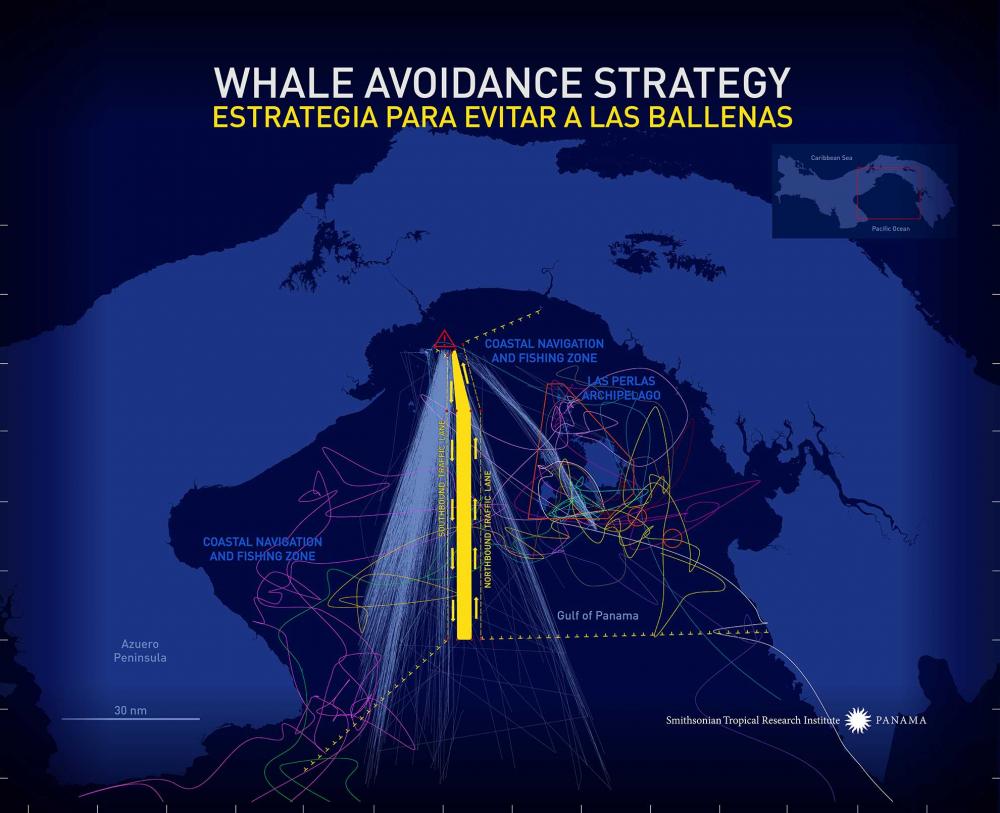

Analyzing movement patterns produced by the satellite tags, Hector noted that as mother whales with calves started to move out of the gulf to begin their return migration home, the pairs stayed closer to the protected coastline. Singles tended to head straight out to sea. But ships were using the entire area of the gulf, increasing the chances of collisions.

Armed with this knowledge about the areas whales tended to frequent, Hector and his team came up with a new strategy to give the humpbacks a new layer of protection.

Modeled after a practice already in place in the United States and Europe, Hector and colleague Captain Fernando Jaen from the Panama Canal Authority suggested a “Traffic Separation Scheme,” requiring ships to travel year-round in two-mile-wide lanes separated from each other by three nautical miles of open water. From August through November, during the critical breeding season, ships would also reduce their top speed to 10 knots. Hector’s models predicted that the drastic reduction of surface area the ships could occupy in the gulf could reduce potential whale-ship collisions by as much as 95 percent.

Working over three years with the Panama Maritime Authority, the Panama Canal Authority, and the Panama Chamber of Shipping, Hector helped local partners steer the policy into law. Approved by the Republic of Panama and adopted by the International Maritime Organization, the Panamanian shipping lanes were implemented in December 2014.

“We didn’t reinvent the wheel,” he notes, adding that the idea of separated shipping lanes has been around since the 1960s. “The novel thing we did was use tagged data to learn more about behavior of whales, and then use that to produce a piece of policy. My colleague Fernando and the Panamanian government were highly engaged to work to make this happen.”

The shipping lanes are also expected to significantly reduce the likelihood of collisions between ships, as well as spills of toxic fuels and cargoes. In Panama, this tactic directly benefits several protected marine areas, wetlands and wildlife sanctuaries in the Gulf of Panama, one of which is a UNESCO World Heritage site.

Other nations such as Costa Rica, Mexico, and El Salvador, as well as other scientific colleagues, have invited Hector to assist with developing similar routing systems for their shipping zones in the coming years. Nations including Ecuador and Peru along the South American “humpback highway” have also expressed interest in adding the lanes, and Hector says he hopes the whales’ entire migratory route will eventually have protections in place—groundbreaking potential for creative scientific inquiry to result in practical policy with far-reaching effects.