Smithsonian’s Agua Salud Project Restores Degraded Landscapes in the Panama Canal Watershed

Jul 18, 2015 | By Isabella Roden

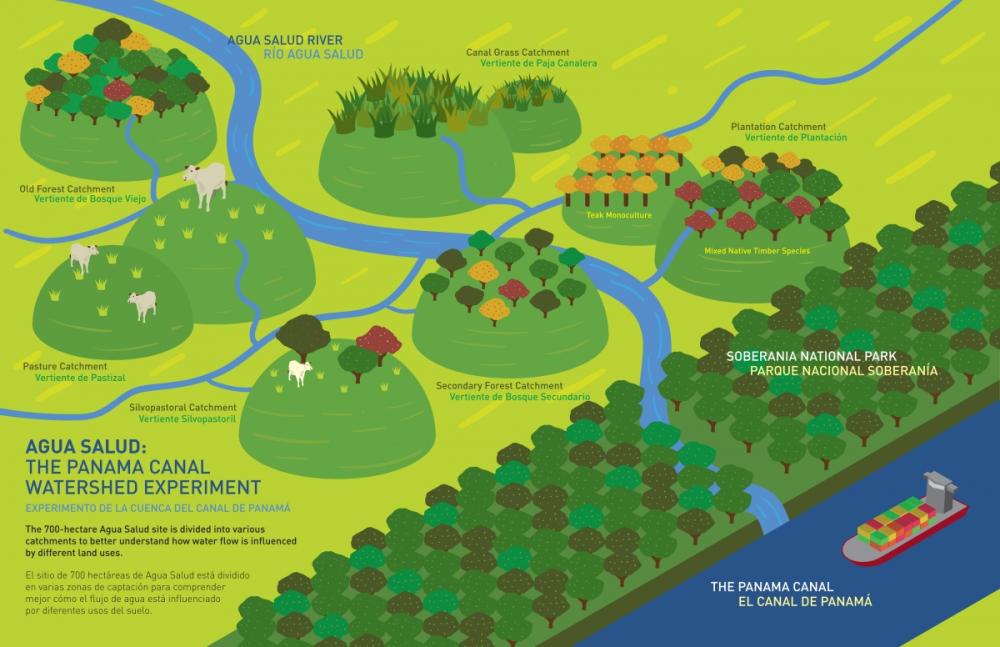

Smithsonian’s Agua Salud Project identifies ways to effectively restore tropical forest within the Panama Canal Watershed that has been degraded through agricultural use. By examining the hydrological, carbon storage, and biodiversity-related goods and services these tropical forests provide, Agua Salud shows the best ways to restore and enhance tropical forests.

Agua Salud provides a model for restoring degraded landscapes to productivity and supports the sustainable management of the Panama Canal Watershed. Smithsonian scientists and their colleagues study how these forests are changing as a result of shifts in land use and global change and how to best ensure long term sustainability.

The Panama Canal is a major site of maritime trade and the Panama Canal Watershed provides drinking water to over 2 million people. As the land within the watershed becomes increasingly urbanized and agricultural practices change, forests that keep local waterways healthy are under increased pressure.

Forests keep waterways healthy. During wet periods they reduce runoff and increase water flow during dry periods. Forests and waterways support tourism and recreational use, and provide habitat for wildlife and fresh water. Tropical forests also help mitigate climate change by capturing and storing carbon.

In the 1990s, Smithsonian set out to document the state of the environment in the Panama Canal Watershed. In 2008, with support from private donors as well as backing by the Panama Canal Authority and Panama’s Environmental Ministry, STRI secured 2.7 square miles of cattle pasture sitting on severely degraded land in the Panama Canal Watershed.

Working with the Panama Canal Authority, Panama’s Environmental Ministry, the U.S. Geological Survey, the University of Wyoming, and other international partners, STRI created the Agua Salud research site to conduct a long-term, large-scale study of how forests provide these services in order to quantify and maximize these forest derived benefits for a diverse group of stakeholders.

One of the early discoveries made through comparing these different watersheds is that forested soil is more porous than cattle-degraded soil. Smithsonian scientist and U.S. Geological Survey hydrologist Robert Stallard, in close collaboration with others, found that porous forest soil acts like a sponge, helping trees to store water in the rainy season and releasing water during dry periods. His research suggests that forested land can better support healthy watersheds, like the Canal, than pastured land. Further work demonstrated that increased infiltration of forest soils substantially reduce flood peaks compared to other types of land cover.

Today, Agua Salud scientists monitor water distribution across the land at nine different experimental watersheds across the landscape. Each watershed represents a different form of land use to be studied, from cattle pastures to secondary forests. Research teams work across diverse fields including hydrology, forest ecology, and even economics.

To determine which types of trees maximize forest services, STRI scientists set out to determine the best way to reforest the land and better support the canal. Non-native teak has been the most commonly used species in forest plantations in Panama. However, Agua Salud research over the past seven years found that selected native tree species can provide more timber in less time and be more cost effective than teak on the nutrient poor soils of Agua Salud. Further they may enhance biodiversity values.

These Agua Salud research findings help policymakers identify strategies to better manage water for local populations and mitigate risks to infrastructure.

“We do fundamental and curiosity-driven science, with a focus on its use and practical application,” says Project Director Jefferson Hall. “We translate science into policy and action.”

Agua Salud research is creating new possibilities for restoring and managing ecosystem services in changing tropical forest landscapes and research at Agua Salud is expanding in scope every day. Scientists plan to use drones to monitor leaf emergence in plantations and secondary forests, lasers to measure how much water leafy plants absorb and then release during photosynthesis, and to install meteorological towers to collect and transmit data. Agua Salud also uses biological surveys to measure how birds and mammals return to and repopulate the regenerating landscape. Using the Panama Canal Watershed as a study system, the research from Agua Salud will be useful throughout tropical America.