Out of Bondage, Research on Slave Wrecks Build New Ties of Promise

Jan 12, 2016

In the colonial slaving era, thousands of vessels traded in misery across the waters of the high seas. One such a ship, the Portuguese São José-Paquete de Africa, left its port on Mozambique Island in 1794, destined for Brazil. It was one of thousands of ships bound for the New World carrying human cargo, a trade that trafficked an estimated 12 million souls over more than 350 years.

Only weeks into its journey, the São José foundered on rocks 100 meters from shore near Cape Town, South Africa. More than half of the 400 enslaved people aboard perished in the violent waves of a hidden reef. Those who survived were resold.

Drowned and overlooked for more than 200 years, the wreckage of the São José suffered the same fate as an estimated 1,000 other ships which disappeared during the slave trading years. But it is unique in that it sank during the slaving leg of its journey, and is the first ship ever to be archaeologically documented that had been carrying slaves when it went down.

A new collaboration between the Smithsonian’s National Museum of African American History and Culture (NMAAHC) and a broad international partnership is helping to unveil some of what was lost. The Slave Wrecks Project (SWP) seeks to bolster the growing field of maritime archaeology and build partnerships between local, national and international stakeholders by focusing on the discovery and study of slave ships.

“When people talk about slavery, they often throw around large numbers like 12 million,” says Paul Gardullo, curator at NMAAHC and researcher of cultural memory and heritage, and a key representative of the museum’s partnership in SWP. “It can have the effect of making the history seem unreal. But the finding of the São José makes this massive story human.”

The Slave Wrecks Project is adding new international voices and perspectives to the story of slavery. By expanding knowledge of the historic and cultural impacts of the global slave trade through the discovery, excavation and study of wrecked slaving ships, the project yields an innovative model for how museums, cultural and heritage institutions and can operate expansively, effectively and collaboratively in the 21st century.

“We want to raise the field,” Paul says. “The people should be invested in this history in their own communities. We strongly felt we needed to build capacity in places like South Africa and Mozambique to do this kind of work professionally, as well as to build institutional capacity to showcase this work.”

Composed of six core partners, including Smithsonian’s NMAAHC, with Iziko Museums of South Africa, the U.S. National Park Service, the South African Heritage Resource Agency, Diving With a Purpose, and the African Center for Heritage Activities the project initially focused on South Africa.

In 2015, SWP confirmed the discovery of the São José, the first-ever archaeological documentation of the wreckage of a slave ship that had been carrying people when it sank. To find the São José, collaborators embarked upon an unprecedented level of research, support and cooperation.

Until recently, little attention had been focused on finding slave wrecks. Most shipwreck activity concerned treasure seekers hunting spoils, or academics looking for military and commercial vessels. SWP, launched as the Southern African Slave Wrecks Project in 2008 by George Washington University researcher Steve Lubkemann, along with Dave Conlin, Chief of the NPS Submerged Resources Center and Jaco Boshoff of Iziko Museums, sought to change that.

Just as the São José once carried slaves from Mozambique to Brazil and points in between, research into the wreckage has reconnected those places, but with the goal of understanding the historic and cultural value of the ship and its stories. The dialogue on slavery grew to include new, previously absent perspectives.

From Mozambiquan and Portuguese archivists digging into their respective resources to research the ship’s history, to Brazilian researchers beginning to connect the recorded names and ethnicities of slaves that arrived there after the São José, an entire network of trans-Atlantic collaboration began to emerge. The partnerships produced new opportunities for professional training in maritime archaeology, community-based anthropological research, artifact conservation, and public education—all related to this single find.

“With the São José, we were able to connect researchers from Brazil to the interior of Mozambique,” Paul says. “Over time, that will not only be compelling to the public but also be a huge contribution to scholarly research in the subject.”

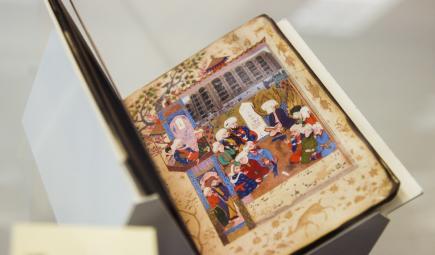

In addition, publicly displaying and interpreting this history through a variety of platforms provides the opportunity for people all around the world to experience and grapple with authentic pieces of the past that played a foundational role in shaping world history.

“Perhaps the single greatest symbol of the trans-Atlantic slave trade is the ships that carried millions of captive Africans across the Atlantic never to return,” said NMAAHC director Lonnie Bunch. “The São José is all the more significant because it represents one of the earliest attempts to bring East Africans into the trans-Atlantic slave trade—a shift that played a major role in prolonging that tragic trade for decades.”

Since 2012, the project has been expanding its scope to reflect the global reach and impact of the slave trade. Collaborators on other projects are now investigating potential shipwreck sites in the Americas, the Caribbean, West and East Africa, and the Indian Ocean. At the Smithsonian, artifacts from the São José will be on display in the new NMAAHC building opening on the National Mall.

“It’s leading us in directions and connecting us to people and communities we couldn’t have predicted,” Paul adds. “Without this broader network of scholarship, we would have never found this level of information. The Slave Wrecks Project group are dedicated to connecting their work not just to the past, but also to the present and future, and these public institutions are playing an important role in helping many different communities hear and learn about these stories.”